Chromatic_Dialogues

Chromatic Dialogues exhibition view © Luca Shoeffel Photography

Chromatic Dialogues exhibition walk through with the curator Dakota Sica

Chromatic Dialogues exhibition view. Artwork: Friedel Dzubas, Eagle Pass,1976, magna (acrylic) on canvas, 72h x 72w in

Chromatic Dialogues exhibition east lobby view. Artworks by Friedel Dzubas

WORKS AVAILABLE

Chromatic Dialogues

Curated by Dakota Sica

March 2023 – June 2024

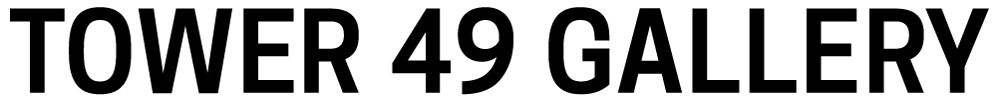

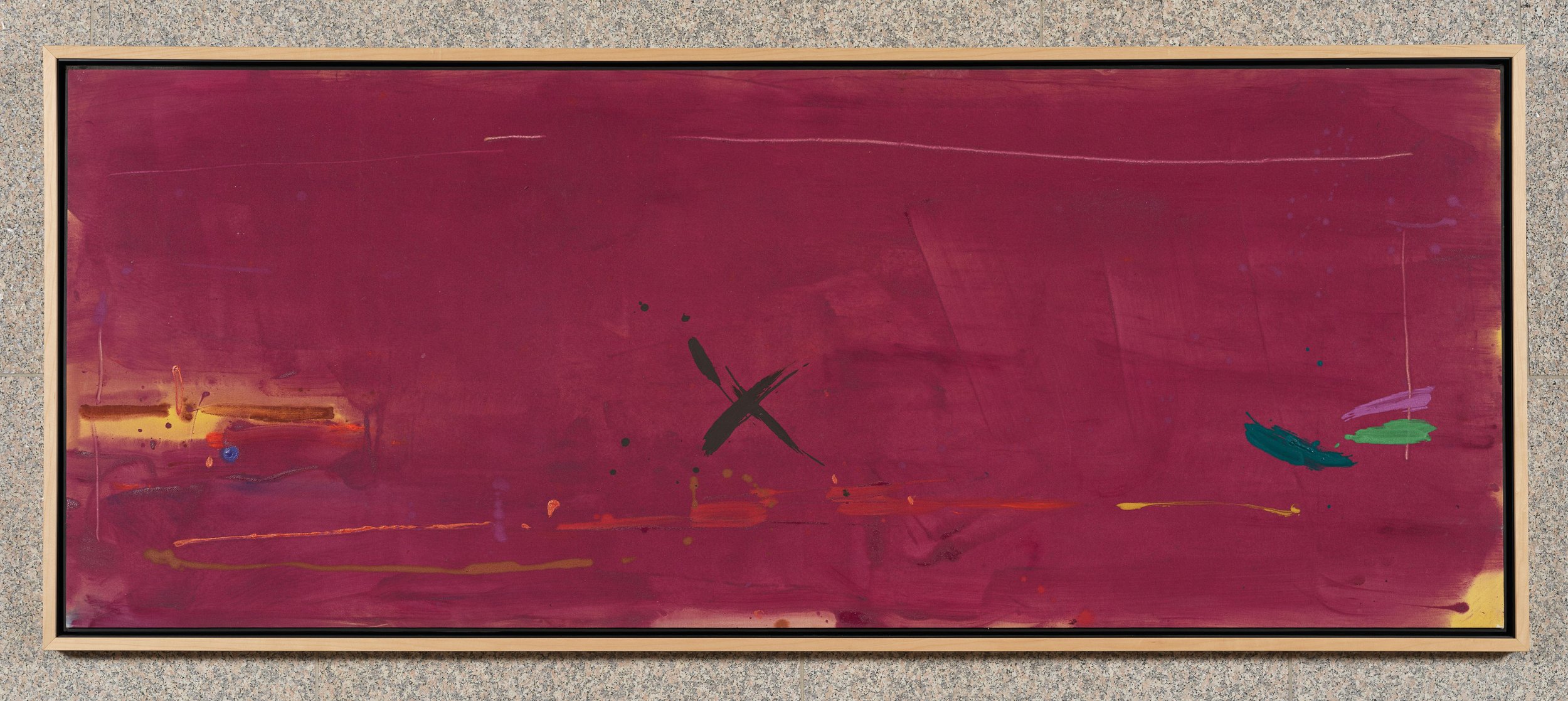

NEW YORK – Tower 49 Gallery is pleased to present Chromatic Dialogues, a yearlong exhibition of Abstract Expressionist and Color Field paintings. Featuring twenty-five canvases and works on paper by six internationally renowned artists — Helen Frankenthaler, Jules Olitski, Robert Motherwell, Cleve Grey, Kikuo Saito, and Friedel Dzubas — the show will open to the public on Friday, March 17, 2023, in the ground-floor lobbies and the 24th-floor Sky Lobby of Tower 49, 12 East 49th Street, New York.

Curated by Dakota Sica, Chromatic Dialogues explores the enduring vitality of Post-War painting, a 70-year legacy that remains key to the art of today. As a gallerist, curator, and collector, Sica takes a long view of art history, immersed in the era of the pioneering abstractionists while championing the work of new, young, and emerging artists. The connection between then and now is underscored by the date range of the paintings on display, from Engadin I by Friedel Dzubas (1962) to Kikuo Saito’s Rhapsody (2015).

The exhibition’s title invokes the swaths of pure pigment that form an intense aesthetic exchange among the works, bridging movements and generations. The paintings of Cleve Gray from the early 1970s unfold like cascading streams of color and light, a liquid dynamism that connects to the brushed-ink drawings on rice paper that Robert Motherwell made in his Lyric Suite series of 1965 (whose title is taken from a string quartet by Alban Berg).

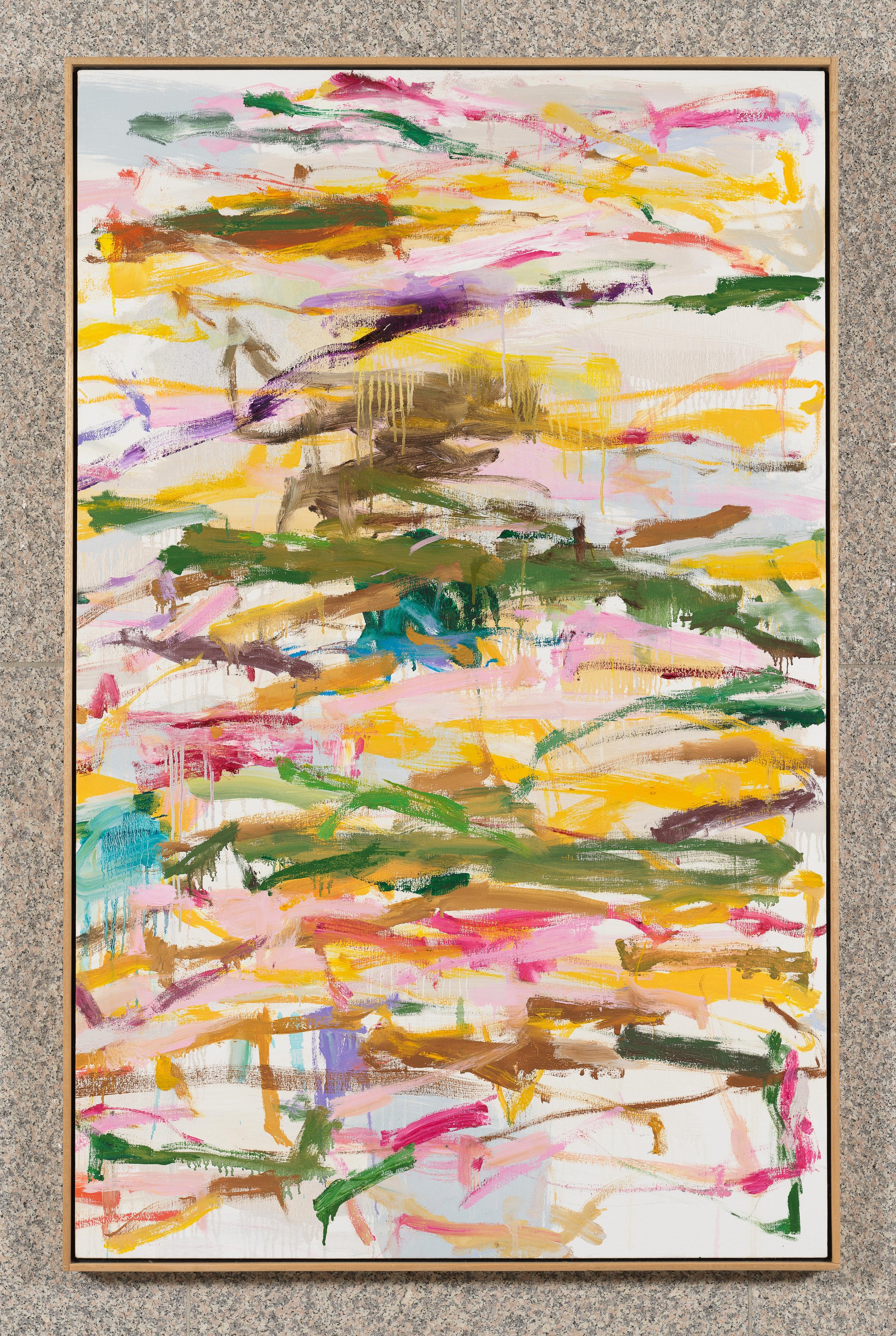

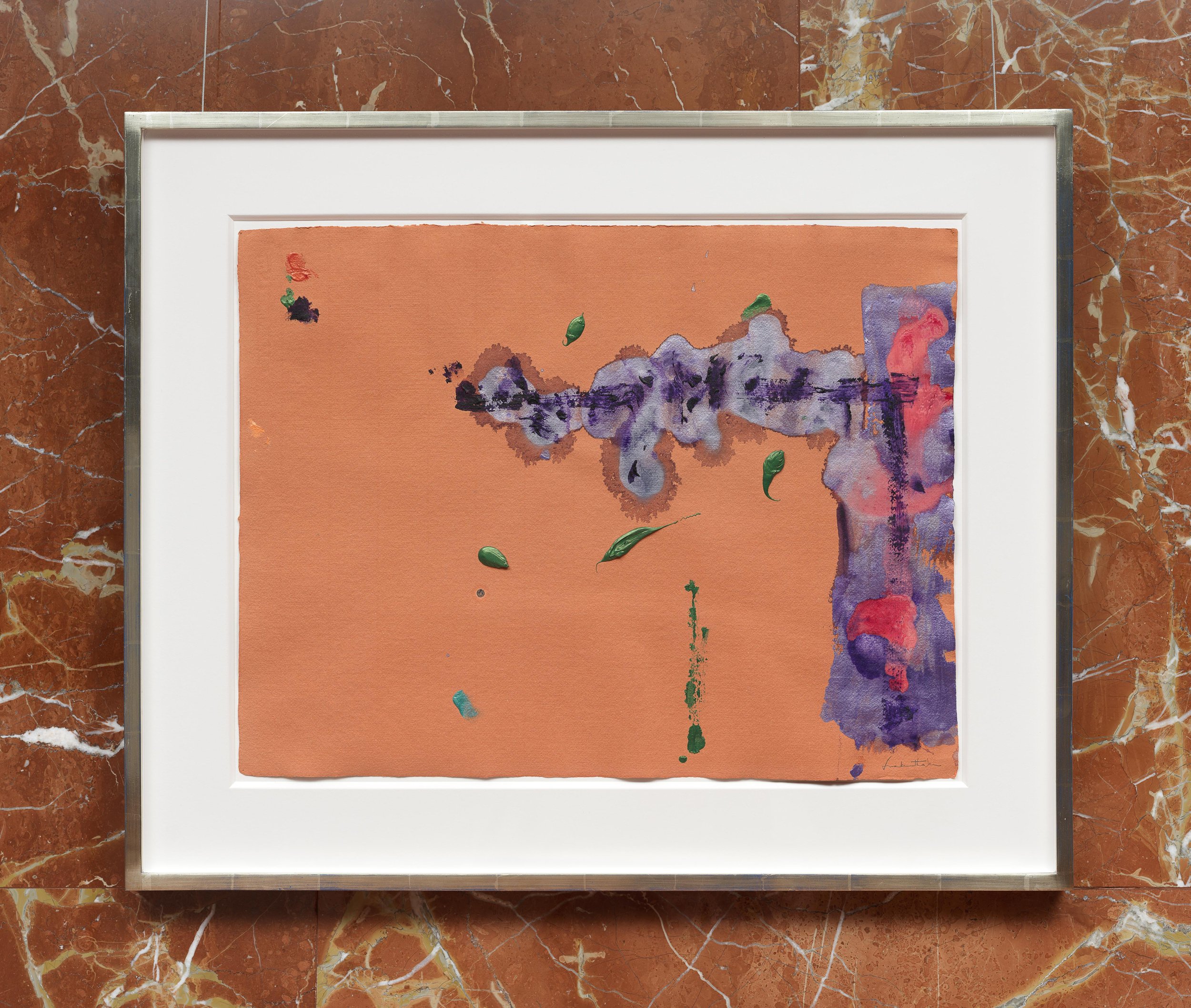

Jules Olitski, whose paintings were the subject of a solo show at Tower 49, is represented by a major early example of his spray period, Gree (1966). The atmospheric quality of its massive upper portion, sitting atop a supporting gold strip, speaks directly to the dominant green passage floating above a pool of red strokes and amber washes in London Memos (1971-75), a large acrylic-on-paper by Helen Frankenthaler.

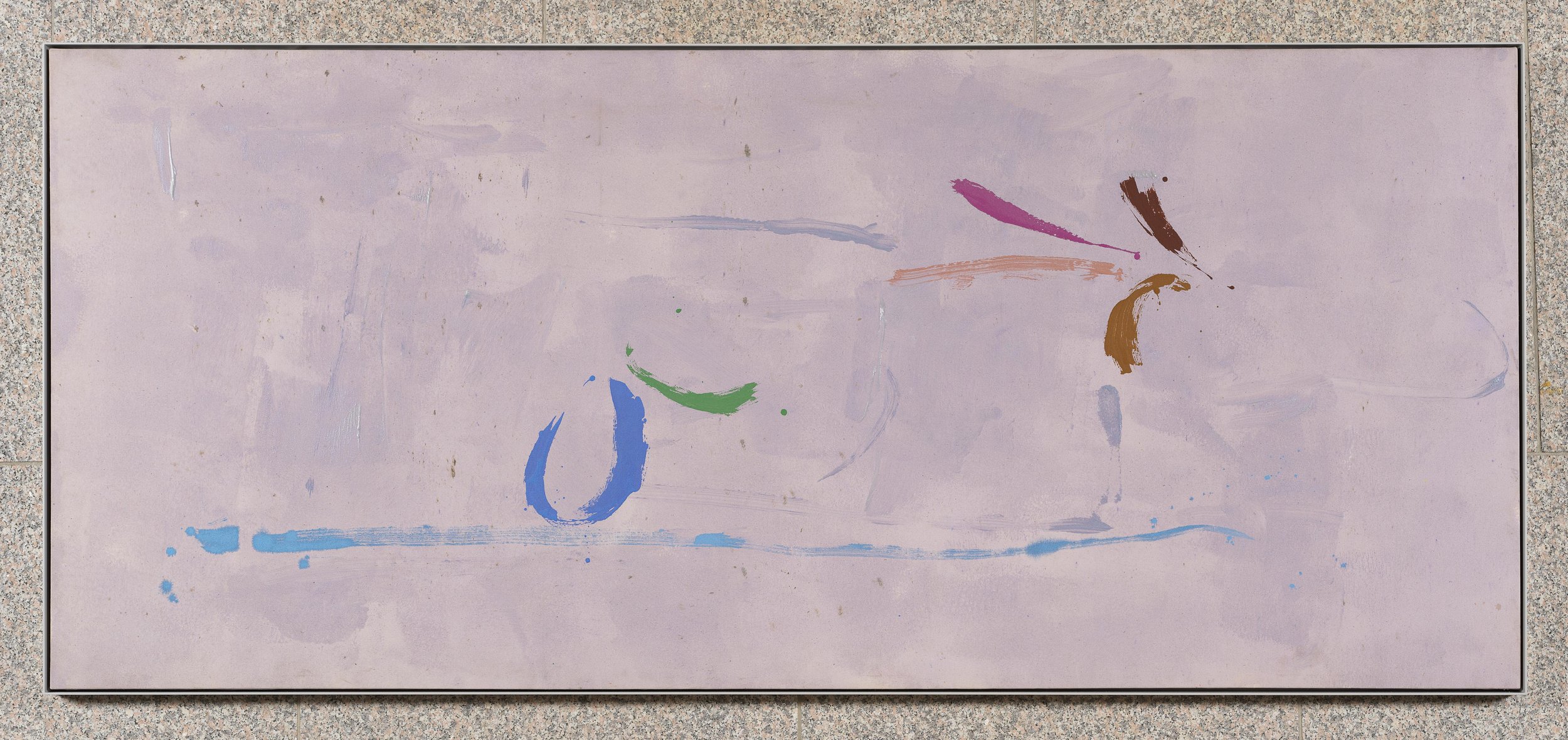

While the works of these four artists were completed within several years of each other, the paintings of Kikuo Saito and Friedel Dzubas span decades. Saito’s seven canvases, painted between 1983 and 2015, trace the artist’s evolution from minimal calligraphic strokes to networks of exuberant brushwork. The early paintings of Dzubas, whose artwork was also the subject of a solo exhibition at Tower 49 — a presentation that included the epic, 56-foot-long Crossing (1975), the largest work the artist ever made — are composed of stable, almost hard-edge forms, but by the 1980s these shapes have loosened into swirling clouds of color, dissolving any distinction between shape and stroke, idea and substance.

DAKOTA SICA is a partner of the Leslie Feely Gallery, located in New York City, and the founder/owner of The Java Project in Brooklyn. He has also been collaborating with Artnet to curate GEMS: Collecting Post-War Abstraction, an ongoing auction series. He currently serves on the board of the International Fine Print Dealers Association and is a member of the Guggenheim’s Young Collectors Council. Sica is an expert in Post-War Art, specializing in Abstract Expressionism and Color Field painting.

Chromatic Dialogues: Frankenthaler, Dzubas, Gray, Motherwell, Olitski, Saito by Karen Wilkin

The first question raised by any group exhibition is why the included artists have been put together. As the title “Chromatic Dialogues” suggests, placing the work of Friedel Dzubas, Helen Frankenthaler, Cleve Gray, Robert Motherwell, Jules Olitski, and Kikuo Saito in proximity is intended to provoke a conversation among them. They clearly have a lot to say to each other, as abstract artists who make color the main carrier of emotion and meaning in their work. But they are also obviously distinct individuals, each with a highly personal notion of what a painting can be. No one would mistake the work of one for the work of another. They belong to different generations and had different backgrounds and formations; some even had their origins in different countries. Motherwell (1915-1991), born in Oregon, was the youngest and the most cerebral of the Abstract Expressionists, while the German-born Dzubas (1915-1994), Motherwell’s exact contemporary, was closely associated with Frankenthaler (1928-2011), a native New Yorker, and the Russian-born Olitski (1922-2007), and like them, was one of the painters loosely grouped under the rubric of Color Field. Gray (1918-2004) could be described as linking the two movements with his gestural, intensely colored canvases. Saito (1939-2016), born in Japan, combined painting, theater sets, and performance in original ways, informed by the legacy of both the Abstract Expressionists and the Color Field artists.

These differences notwithstanding, the six artists also have much in common. Since all of them lived and made art in or near New York during their entire working lives and showed in New York galleries, they were all part of the New York art world of the time – a far smaller constellation of painters and sculptors than it is today, one with many overlaps and connections that transcend age and background. Dzubas and Frankenthaler shared a studio in 1952 and 1953. Frankenthaler and Motherwell were married from 1958 to 1971 and, in those years and after, were good friends with Gray and his wife, the writer Francine de Plessis. Saito was Frankenthaler’s studio assistant for a short time. Olitski, Frankenthaler, and Motherwell exhibited in the same galleries. And more.

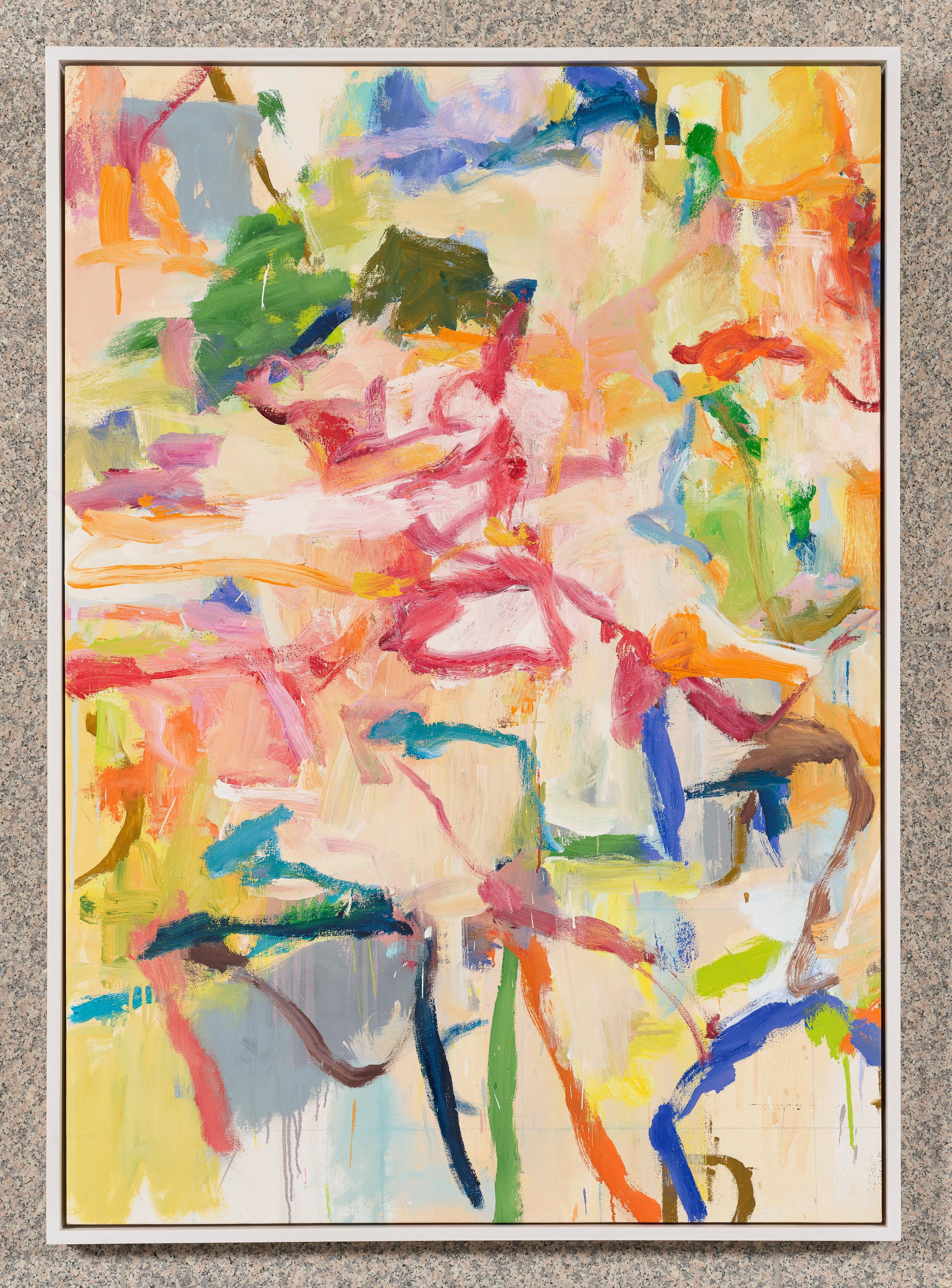

While these friendships and cross-connections are important, what is more significant – and immediately visible in the works on view – is that the six painters shared aesthetic convictions. Their work was rooted both in the assumption that the artist’s role was to reveal the unseen, not to report on the visible, and in the firm belief that paintings were driven by the artist’s inner imperatives. Each of the six – including Motherwell – rejected the wet-into-wet, angst-driven approach of gestural Abstract Expressionism, as exemplified by de Kooning’s juicy canvases, so prevalent among the next generation that the critic Clement Greenberg coined the derogatory term “the Tenth Street touch.” Frankenthaler, who famously observed that while you could become a disciple of de Kooning, you could depart from Pollock – as she did.) Motherwell was always a master of generously scaled drawing, but from the start, he eschewed layering and dragging one color into another, preferring a more anonymous surface and graphic clarity. Motherwell’s collages, which depend on placement and physical differences, bear witness to his fascination with ready-made materials but are equally graphic. Like him, the other artists in this exhibition were acutely sensitive to the expressive possibilities of their media (and took advantage of the evolving capabilities acrylic paint, over the years), yet the surfaces of their paintings are mainly uninflected and thinly painted, to emphasize the visual. Often paint is applied in unconventional ways, by pouring or spraying, or with rollers or squeegees, allowing for seamless shifts of color and very large scale drawing, as well as, on occasion, expanses so disembodied that they seemed to detach color from materiality. In the 1960s, Olitski adopted the spray gun to realize his declared wish “to have color hang in the air.” Frankenthaler stained, poured, used sponges, and her hands. Brushes, when used, as in Dzubas’s and Saito’s paintings, provide testimony to athletic, full-arm movements – sweeps of paint that fray off at the end and eloquent, illegible calligraphy. All six artists thought of the canvas or the sheet of paper as a flat expanse that could be activated, edge to edge, by their interventions, an attitude that ultimately derives from Jackson Pollock’s all-over webs and skeins of pigment.

The paintings in this exhibition claim our attention most immediately with their radiant color and their declarative, confrontational compositions, a description that is as true of Frankenthaler’s compelling works on paper as it is of Olitski’s ample, mysterious sprayed canvases or Saito’s webs of ribbony strokes. All the works in this exhibition could be described as beautiful, a much maligned word, these days. All six artists depend on the potency of color and relationships of color and shape to address the viewer’s entire being – emotions, intellect, and all – through the eye, as music does through the ear. (Obviously, any work of art worthy of the designation, whether containing recognizable images or not, is loaded with the artist’s individual accumulated baggage, including his or her relationship to other works of art, and viewers will filter whatever they encounter through their own prejudices and associations.) The more time we spend with these works, the more we discover in them, as we become increasingly aware of nuances of color, variations of tone, differences in edges, and subtleties of placement. We discover ambiguities, as, for example, large areas of color that simultaneously suggest infinite, boundless space and remind us of the flat surface of the canvas. There’s a lot to look at.

What we will not find is irony. All six artists were passionate about what they did and cared deeply about making paintings that were alive, that spoke to us, wordlessly but powerfully. Neither will we find overt references to politics or sociology or ecology or social justice or any of the other important issues that art is supposed to address, these days, if it is to be taken seriously. All six were seriously engaged by the world they lived in, but they did not believe that paintings could right egregious wrongs. Marcel Duchamp, who was made uneasy by what he called “aesthetic delectation,” claimed that he wished “to carry the mind of the spectator toward other regions more verbal,” forgetting, it seems, that the eye is part of the brain. Dzubas, Frankenthaler, Gray, Motherwell, Olitski, and Saito all valued the visual more than “regions more verbal.” Aesthetic delectation is not a bad thing.

TOWER 49 GALLERY, one of New York City’s most unique and striking contemporary art spaces, offers exhibitions free and open to the public in the street-level lobbies and on the 24th floor of its Skidmore, Owings and Merrill-designed building. Spearheaded by Ai Kato, Exhibition Director, the gallery’s mission is to originate exhibitions that challenge conventional ideas about public art, featuring such internationally acclaimed contemporary artists as Friedel Dzubas, Frank Stella, Mark Di Suvero, Shigeno Ichimura, Jules Olitski, Cordy Ryman, Michele Oka Doner, and Enrico Isamu Oyama. Tower 49 provides a sanctuary of contemplation in an extraordinary space for the public to discover the important role that art plays in our daily lives.

The exhibition is organized in collaboration with Mark Deutsch.